Dr. Joanna Simos, Associate Director, Arcadia University Athens

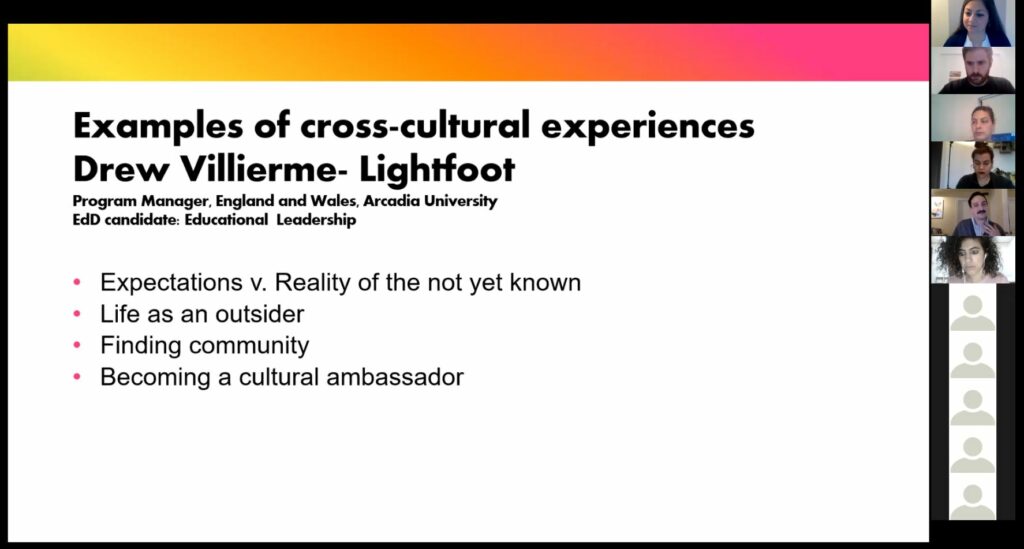

Drew Villierme – Lightfoot, Study Abroad Program Manager, Arcadia University, USA

Building on their combined 20-year experience supporting students through preparation and the experience of study abroad, their research and lived experiences, the writers, Dr. Joanna Simos and Drew Villierme Lightfoot offer critical insight into the many levels of cultural adjustment that include culture shock (CS) and offer advice on navigating the excitement of cross-cultural travel.

In March of 2020 and on a global scale, many of us experienced a challenge to all that we considered constant and certain. Ranging from the way we communicate with others and how we work to how we express affection physically and even the ways we enter our homes. This disruption to daily reality and extended isolation, resulted in feelings of challenged disconnect for many, placing the experience neatly into the chaotic confines of culture shock.

CS is a single, static dimension of the multilayered social and psychological processes the human mind goes through when faced with an entirely new experience, culture or environment. These processes of cultural integration are complex and culture shock forms one of the possible stages. This makes it imperative that we discuss CS, we consider it within the context for cultural integration.

Cultural adjustment and how it evolves for an individual is primarily informed by the circumstances of the change or migration that stimulates us into experiencing what we describe as culture shock. Our discussion explores the stages of cultural adjustment in the instances of voluntary travel. So we are exploring the cultural journey for people who have made the choice to travel, perhaps they are professionals, migrate to have a family or have decided to take their studies abroad. For each of us who travels, there are a number of stages that evolve culturally. Taking the student as our example, typically any of our travelling students will experience one or two of these phases and not necessarily all of them.

We usually expect that the honeymoon phase will be significant, due to the excitement, enthusiasm and prior knowledge lasting from a few minutes to a few months – and it could begin anywhere! On the plane, upon arrival or following an exciting cultural experience.

The plummet, or dramatic change from the honeymoon phase to culture shock is pretty fast. This is the most frequent detail shared among students. During this stage, which we expect to last from approximately two weeks to a couple of months, the discomfort sets in. Feeling distressed for example, the unpleasant part of the process.

A short while after this experience and frequently feeding into the stage that follows, we have reintegration. This is typically a conscious effort, that is to say we would be trying to spread out into our immediate community, trying to reestablish that sense of belonging. A single student may reach out to peers in their study program, socializing within this frame is typical with a small disconnect to the broader cultural environment.

The stage of autonomy follows, where we realize that though we may belong to our immediate community we can operate independently. This manifests in individual travel, for example, or a breaking up of a large social group into smaller numbers. Confidence can be described to have evolved for our student at this stage, leading toward a greater comfort in interacting socially with the broader cultural context, the host country.

The adaptation phase is frequently thought of the ideal perspective in terms of interaction and experience in a new global setting. Having engaged comprehensively and experienced the challenges and evolution of integrating culturally, having consciously considered our personal situation in relation to our new environs we find ourselves rewarded with a newfound comfort with the new, we still face challenges but the way we handle them is now more skilled.

Like all cycles, cultural integration may end in the phase of reentry but this also signifies a new cycle, a new evolution for us personally based on who we have now become having experienced a new culture.

Though we may not be fully aware of the cycle developing during our experience, we are much more alert to how our social relations change and evolve and to how we respond to these changes. Similarly, we frequently become aware of these stages through experiences we learn anecdotally from other, displaced parents for example who changed their homeland, friends who have travelled, discussions of cultural stereotypes. Interestingly, it is sometimes this familiarity with culturally integrative experiences like this that pose a challenge as they set precedents for us, a kind of bias on how we perceive and embody our personal experiences and they can also become a barrier. Systematical preparation can be remedial.

The readily accepted definition of culture shock is a sense of confusion and uncertainty. Sometimes accompanied by anxiety (Merriam – Webster, 2020).

From an educational, social and psychological perspective, this is quite a minimal definition. For example, there is a significant neurological impact for those experiencing culture shock. There may be physical symptoms of distress. The transformation of the stages of cultural integration has a permanent impact. And of course, no two individuals will ever share an identical experience.

Culture shock can feel like your emotions have been numbed, you may become irritable or homesick. You may experience feelings of helplessness, disorientation and sadness. Anxiety and difficulty sleeping may also become part of daily reality, while a shift in our appetite and ability to concentrate can also be expected.

Observing others, we may find that someone experiencing culture shock seems to communicate emotively or apathetically. Has become alienated or critical of the host culture. They may look like they are challenged by their daily routine or express naivety and ethnocentric tendencies in regard to the new cultural context.

It is important to highlight here that though culture shock can be overcome with the support of friends, instructors and family, it could also be signifying the beginning of a significant mental health challenge. If you personally feel overwhelmed or see that someone you know could do with some help, reach out to them, an instructor, member of staff or professional for help immediately.

So far, we have discussed the characteristics of culture shock and the challenges embedded within the process. However, cultural integration comes with many rewards! Culture shock affects the majority of individuals who travel to a new place. It is as likely to impact the seasoned, experience global professional as much as the student who leaves their home state for the first time. Though many theories exist surrounding susceptibility to cross-cultural experiences and the type of individual that may conquer these challenges, we believe that there are two things that can help and prepare us constructively: the management of expectations and preparation leading up to the experience.

Expectations versus the reality of the not yet known: Your experiences of what life and your experience will be like in the new culture may differ from what you expect. Many people imagine that life will be less challenging abroad for many reasons. Maybe they already speak the language of their new location, even if you do, it is doubtless that you will not experience challenges around culture shock. You may not have the local accent, or share other cultural norms of the community that you are living in. For folks who share heritage with eh local community but may have been raised elsewhere, this can be a common challenge. They still may be seen as an outsider, questioned for why they are not fully fluent, as they may be expected to be. They may have other cultural traits that set them apart from the local community. Drew’s experience in Korea demonstrated this was a big challenge for Korean- American friends. They were expected to act, speak, dress and fill the part of a native Korean but faced the challenge of blending in. Connecting with others beforehand to learn how they have experienced the local community can help you prepare for what is ahead. Explore YouTube and other online forums and do some research before departure.

Life as an outsider: For many American students, studying abroad is their first experience as the other, an outsider. The way you look, your skin, your hair colour, the way you carry yourself. Your clothing, your accent and outward appearance may signal that you are not a local. This is particularly challenging for the student staying in their host community for a long amount of time. . Fully integrating into the local culture can feel impossible! You should expect to be uncomfortable and to feel out of place. You may not be ‘in’ on the cultural references and may feel isolated, excluded and exhausted. These are common experiences. And it is part of the cultural integration cycle, culture shock in particular.

Finding community: Solace can be found in connecting with others who have shared interests. Seek out others who share your profession, interest and hobbies. Frequent places where you might meet them. Galleries for those interested in art for example, or a café frequented by expats if you would like to get to know more people from your home country. Connecting with others facing the same experience with you is very useful in helping you bridge that gap in order to find your place within your host culture.

Becoming a cultural ambassador: regardless of why people have travelled to their new location, they are frequently expected to actively represent their home culture. This may be your first experience feeling like you have to be a cultural ambassador. You may feel pressured to do so, for example, by explaining the political situation in your home country. Reconnecting with your initial reasons for studying abroad can help you get past this challenge. Embracing the unknown and expecting this perception of you can help you manage your expectations. When you return home, you may experience the opposite phenomenon in wanting to share and represent your host culture.

A sense of community is clearly dominant in affecting our sense of belonging and can help through culture shock. To help a little more, we have compiled a few useful tips to support you through your cultural integration:

- Create a daily routine

- Use the resources available to you, map apps for example.

- Keep connected to your new environment

- Embrace the idea of the challenge!

- Recognize the new skills you are developing

- Include relaxation in your routine

- Exercise, eat well and hydrate

- Initiate social contact

- Try to avoid criticism

- Be patient in finding your new identity

- Don’t hesitate to reach out for help! Friends, colleagues, supervisors or mental health professionals can help you navigate your cultural experience.

- Seek professional help if you or someone you know needs professional support

If you are working with individuals who may experience culture shock,

- Prioritize support for vulnerable social groups

- Prepare your participants and raise their awareness

- Offers support with care!

- Establish relationships and cultivate access to the resources available

Would you like to reach out to either Joanna or Drew? We would be happy to hear from you!

About Dr Joanna Simos: Awarded the 2018 ‘recognition of excellence in academia’ National Education Research Institute award for offering value added experiences for US students interning in Greece, Dr. Joanna Simos is a lecturer at Arcadia University in London. Having previously served as Associate Director for Arcadia in Greece for 15 years, she teaches Intercultural Studies, Psychology, and Sociology. An active academic and researcher, her published works include studies of Learning Online, Displacement and Applied Pedagogy in South India, Lifelong Learning in Nepal, and the emerging pandemic impact on learning and instruction globally. Dr Simos recently completed her tenure at the European Commission as Senior Education Consultant for the Euro- Mediterranean SRSP and is a reviewer for several global academic journals. An Education Psychologist, Dr Simos is the Founding Director of Polymathea Education Consultants. Joanna particularly enjoys working with students and supporting them as they navigate their individual, distinct paths!

About Drew Villierme-Lightfoot: Drew is a Program Specialist, Global Access Programs at the University of California, Berkeley. An Ed.D. candidate in Educational Leadership, Drew’s research focuses on the systemic barriers that exist in Higher Education and Study Abroad. Drew has extensive experience in assisting students in preparing themselves for overseas study. Drew has worked at several U.S universities and with in-bound language learners as an ESL instructor and with outbound US undergraduates as an education abroad administrator. He has served as a faculty leader on a short-term study abroad program in Japan. He has professional interest in the intersection of identity and international education and is active in working groups and committees to better support diverse students on global learning experiences. His future research examines the perspectives of students experiencing institutional pressure to study abroad.